24-05, Audit of the Department of Human Services’ Child Welfare Services Branch

Posted on Apr 22, 2024 in Summary|

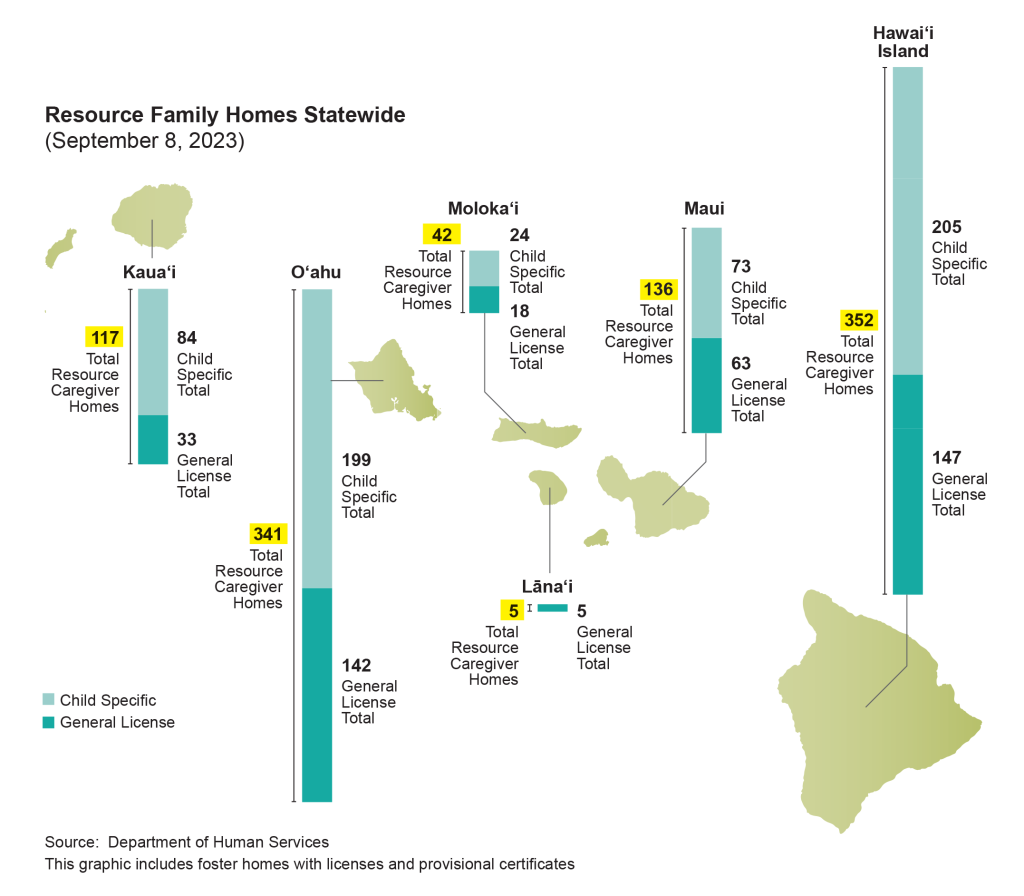

AUDITOR’S SUMMARY Report No. 24-05 THE DEPARTMENT OF HUMAN SERVICES (DHS) is charged with providing services “for the protection and care of abused or neglected children and children in danger of becoming delinquent to make paramount the safety and health of children who are harmed or are in life circumstances that threaten harm.” The importance of that responsibility – protecting Hawai‘i’s keiki – simply cannot be overstated. When children cannot remain safely in their homes, DHS’ Child Welfare Services Branch (CWSB) places children in foster homes, which the department refers to as resource family homes, until those children can be reunited with their families or placed with adoptive parents or legal guardians. Foster homes must have a license issued by the department to care for a child. The licensing requirements are contained in the administrative rules promulgated by DHS and are the standards of conditions, management, and competency that the department determined foster homes must meet to provide a safe, stable, and nurturing environment. DHS recognizes two types of foster homes: homes in which the caregivers have no relation to the youth they foster, referred to as general license homes, and child-specific homes where the caregivers have an existing relationship with the child. While the licensing requirements are the same for both types of homes, only general license homes must be unconditionally licensed before children are placed in the home. DHS can issue provisional certificates, which are temporary licenses, to child-specific homes to allow foster children to be placed in those homes while the homes complete the licensing requirements, which include FBI fingerprint background checks, medical clearances, and home studies. By law, the provisional certificates are, generally, not to exceed 60 days and can only be approved by DHS “if it is reasonable to assume that all licensing requirements will be met within sixty days and that there are no risks to the health, safety, or well-being of a child.” To expedite foster home licensing, DHS has contracted with Catholic Charities Hawai‘i (Catholic Charities) to perform the home studies and compile the documentation necessary for the department to license the homes. For contracts relating to health and human services, such as DHS’ contracts with Catholic Charities, the law requires DHS to “formulate and implement a monitoring plan” for those contracts, which includes, among other things, “a manual or other set of guidelines” describing the objectives, procedures, and requirements of the department’s monitoring process. DHS is also required to develop criteria and procedures to evaluate contracts after they expire or are terminated. What we found We found that DHS allowed children to be in unlicensed child-specific homes, i.e., those with only provisional certificates, for many months, sometimes even more than a year, by approving multiple consecutive provisional certificates to the same home. Our random sample of roughly 10 percent of CWSB’s “active” licensing files included 30 child-specific homes. None of those homes completed the licensing requirements within 60 days, and none of the children in those homes were removed, as directed under DHS’ licensing procedures. For those homes in our sample, the licensing process took an average of 314 days. Many child-specific homes had been caring for foster children for more than 60 days but had not completed the licensing requirements as of the date on which we reviewed the department’s files. For example, DHS had approved multiple provisional certificates to one of those homes that covered 720 days – and counting. We found that CWSB extended or issued additional provisional certificates and often retroactively dated those certificates to cover periods when children were in homes with expired provisional certificates. This common practice allowed children to stay indefinitely in homes that had not, and in some cases could not, meet the requirements that DHS, itself, had established to ensure that homes were safe. CWSB also did not monitor or evaluate Catholic Charities’ performance to ensure the services the State paid for were delivered. In fact, Social Services Division staff involved in contracting were unaware that they were legally required to do so. Although DHS was aware Catholic Charities was underperforming, it continued paying the contractor’s invoices and, in 2023, extended Catholic Charities’ licensing contract, and a separate support services contract, for another two years. The contract’s payment structure is “cost reimbursement,” where the State pays Catholic Charities up to $2 million per year, essentially reimbursing Catholic Charities’ personnel and administrative costs associated with the contract. However, reimbursement of those costs is expressly conditioned on Catholic Charities satisfactorily delivering the services required in the contract. We found that DHS reimbursed Catholic Charities’ costs without regard to performance of the services; the department’s payment process effectively removed the requirement that the contracted services be “satisfactorily performed.” Why do these problems matter? The department, through CWSB, is responsible for “the safety and health of children who have been harmed or are in life circumstances that threaten harm.” Requiring homes to have licenses issued by DHS is one of the policies that the department included in its administrative rules to perform that critically important responsibility. However, unless a home completed the requirements and was awarded an unconditional license, DHS did not know whether a home was a safe and healthy environment and children in that home were at risk of harm. According to the CWSB Administrator, “The expectation is that these children will be in homes that will keep them safe … I think we follow the rules, and we try to do our best with that, and on occasion, children are being hurt in those homes.” By disregarding and overwriting the policies and requirements in those rules, DHS’ approach, which allowed children to be in unlicensed child-specific homes much longer than 60 days, seemed to prioritize factors other than the safety and health of the children under its care and increased the risk that children might be harmed in those homes. And, that risk is not simply theoretical. We found a number of cases, which are described in the report, in which children in child-specific homes operating under multiple consecutive provisional certificates were actually harmed. In addition, the State lost a significant amount of Title IV-E federal funds. Those funds, which reimburse the State for eligible foster care payments, are accessible for payments to licensed homes; the State was not able to claim the Title IV-E funds for foster homes with provisional certificates. With respect to the contracts with Catholic Charities licensing support services, one purpose of which was to expedite the licensing of child-specific homes, DHS did not hold Catholic Charities accountable for performing the services under the contract. As we found, DHS’ licensing of child-specific homes was neither expedited nor in accordance with legal requirements. Without any monitoring program and confusion between offices as to which was responsible for ensuring performance of the contract, DHS essentially reimbursed Catholic Charities’ personnel and administrative costs without ensuring that satisfactory performance of the services. That approach resulted in a waste of state funds. |